Gloriously alive: making music in 1931 and 2016

I made a pilgrimage recently to this unassuming building, just off the Portobello Road in London. Why? Because it embodies the spirit and determination of a group of composers and performers who – denied a more conventional platform – created their own space for new music.

I made a pilgrimage recently to this unassuming building, just off the Portobello Road in London. Why? Because it embodies the spirit and determination of a group of composers and performers who – denied a more conventional platform – created their own space for new music.

I have been moved to tell their story by the inspirational initiative of the London Oriana Choir whose five15 series will offer something as exciting and something, sadly, as needed in 2016 as it was in 1931. You can find out more here!

This building matters because…

The young composer Elizabeth Maconchy, fresh from success in Prague, and a Proms debut in the summer of 1930, was finding it hard to get her music played. The lack of a career infrastructure and performance opportunities for all young composers was exacerbated for women by good old-fashioned sexism in the classical music industry. Even after the triumphs of 1930, Maconchy later recalled no one

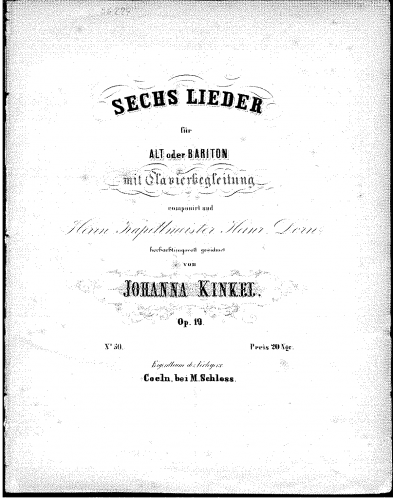

suggested a commission, or a grant, or even a chatty interview on the radio, let alone another performance. The publishers weren’t interested. They were all men, of course, and tended to think of women composers being capable of only the odd song or two.

They would have ‘liked some pretty little thing – I don’t mean a pretty little person – not steady, serious music.’ Maconchy singled out Lesley Boosey, of Boosey and Hawkes, as particularly hostile. One of Boosey’s readers ‘was frightfully keen to publish some songs and a string quartet’ of her, but ‘all Boosey would say was that he couldn’t take anything except little songs from a woman.’ Later, using her typical understatement which masks but does not completely hide her bitterness, she would say ‘that really was a very difficult thing to get over.’

But she did – with a little help from her friends.

Faced with the intransigence of the music industry, a remarkable group of women got together in 1931 and changed the face of music in London, at least for a few years. One was Iris Lemare, that rare thing a female conductor. The other two were the violinist Anne Macnaghten, and the composer Elisabeth Lutyens. Together they launched a series of concerts to showcase new music by young composers, alongside works from eras under-represented in the concert halls of London at the time. The Macnaghten-Lemare Concerts were to prove a lifeline for Elizabeth Maconchy through the 1930s.

And this is where the building comes in – the small, necessarily cheap Ballet Club theatre in Notting Hill, once a Ragged School would be their venue. It had been bought in 1927 by Marie Rambert’s husband as a performing and rehearsal space: the blue plaques today honour Rambert. There is no acknowledgement of the Macnaghten-Lemare initiative.

The women’s methods were collaborative and informal, with no committee, no hierarchy, just the drive to create a platform for their own work, whether as performer, conductor or composer: ‘honestly,’ remembered one of the organizers, ‘it wasn’t altruistic, it suited each other’s ends.’ Anne Macnaghten, who shouldered much of the organizational responsibility, was, however, eloquent about the driving vision, her words relevant to the world of music, past, present and future: ‘the great thing is to have lots of music going on all the time, lots of things being performed.’ Committees might set themselves up as arbitrators as to what is good and what is bad, but the thing is – get the music played, and

it will settle itself sooner or later. As long as there’s plenty of opportunity to get new works performed, no harm will be done; what is awful is if somebody is really doing something very good but nobody knows about it.

I could dwell on the predictable (and sexist) responses to the concerts, I could ask why they seemed to help a very young Benjamin Britten launch his career, but offer yet another dead end to the women involved, but – on the day on which my book is published in the United States, I’m determined to be optimistic. So I’ll leave the last word to the Musical Times:

there is nothing quite like these concerts in London. The concert givers get to grips with the real thing in a most delightful, unconventional way, and after an evening spent with them one feels that music is gloriously alive.