Danger: female violinist at work

Here’s the lovely Nicola Benedetti. It’s hard to believe now, but there was a time when many people were disgusted at the sight of a woman playing the violin. As one writer (in The Girls’ Own Indoor Book, attempting to reassure teenage girls in the 1880s) says

I have also in former days known girls of whom it was darkly hinted that they played the violin, as it might be said that they smoked big cigars, or enjoyed the sport of rat-catching.

By the end of the century, those former days appeared long gone. Violin-playing was deemed ‘lady-like’, if not a suitable job for a woman – when Henry Wood, the visionary director of Queen’s Hall Orchestra and the man behind the Proms, hired six female string players in 1913 he was right to take great pride in his action, but, sadly, other orchestras did not follow suit.

So why did violin playing cause horror in so many? Because it involved what was seen as a distortion of the proper (aka ‘natural’) posture of a woman’s body. To play the violin the woman had to bend her head, use rapid arm movements, both of which were not deemed appropriate to her sex. Gradually, these views changed. So long as the woman remained properly feminine, then she could, and did, play the violin.

But this is where it gets more complicated. A deeper taboo emerges when women become expert at the violin. The violin was itself (herself) understood as female, with its softly curving shape, its belly, back, waist and neck. The real-life woman gets to play the instrument-woman with a stick. A stick. Apparently – and I’m relying on the finest of musicological sources here – the modern bow, which emerged by the end of the eighteenth century in all its sleek concaveness, lessened the connection with archery, but increased its eroticism. I am not one to judge, being a pianist, recorder player and one-time clarinettist. (Don’t even go there.)

No wonder then that the male violinist was often understood as a masterful lover of

his [sic] delicate, exquisitely responsive, and beloved instrument, a perception heightened by the soloist’s caressing arm movements and facial expressions, sometimes accompanied by closed eyes, suggestive of inward joy or ecstasy.

The performer Sarasate, we are told, ‘weds his violin each time he plays…’ with a ‘spirit of ardent love’. Yehudi Menuhin, himself one of the great, and fortunately for him, male, violinists of the twentieth century, said that the violin’s shape is ‘inspired by and symbolic of the most beautiful human object, the woman’s body’ and therefore must be played by a ‘master’.

Menuhin (and he was not alone) was genuinely worried about what happens when a woman plays upon her own body.

Does the woman violinist consider the violin more as her own voice than the voice of one she loves? Is there an element of narcissism in the woman’s relation to the violin, and is she, in fact, in a curious way, better matched for the cello? The handling and playing of a violin is a process of caress and evocation, of drawing out a sound which awaits the hands of the master.

Put a large cello between your legs, darling, and leave the fiddle playing to the boys seems to be the message here.

That was then, this is now. Or is it? A quick google of male violin virtuosos and female violin virtuosos suggests that the old fear of being seen as un-feminine (rat-catching, cigar-smoking) generates a particular kind of image of the female violinist. Further, the traditional erotics of violin-playing produce sexualised images of women and her instrument. The female violinist is never quite the ‘master’.

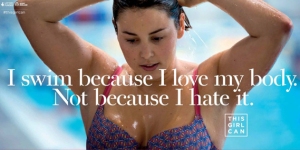

Similar anxieties emerge in women’s sport. Yes, 55,000 people watched England play Germany at Wembley. England Women. 55,000 people watching women play sport is great news – I should add that the result was less good news – but do have a look at this article about the changes in women’s football, and hear the echoes of the musical world: http://www.theguardian.com/football/2014/nov/21/women-football-britain-wembley-england-v-germany. More recently, Sport England have launched a inspirational campaign to persuade more women to take up sport, tackling head on the issue of women’s bodies: https://www.sportengland.org/our-work/national-work/this-girl-can/.

This girl can.

It’s a great tagline – although most of us are not girls. And there are some powerful images.

How does this link with my writing? Because, despite working in the shadow of the courtesan, each of the eight composers I am writing about sent the same message to their contemporaries:

this woman can….compose.

That’s why I admire them so much.

interesting and great!!!